This post is a discussion of the paper Evolutionary games and spatial chaos by Martin Nowak and Robert May. There is also this repo with code for reproducing the paper results and this blog’s visuals

Play the Spatial Prisoner's Dilemma game

Configure the control panel below and watch a population of agents playing the game.

Paper examples | Make your own configuration | |||

| Configurations of the hyper-parameters that give interesting dynamics | Benefit of cooperation: | Percentage of initial cooperators: | Number of rounds: | |

| | ||||

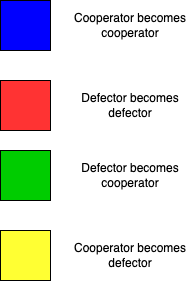

| What do the colors mean?  |

“Evolutionary games and spatial chaos” is a foundational paper in adaptation in multi-agent systems. It is also one of the works that majorly contributed to forming the field of complex systems. The mantra here is: “complex patterns arise out of the interaction of simple parts”. You may have seen complex patterns in other types of complex systems in computer science, such as cellular automata. Although they are conceptually different, spatial games may remind you a bit of cellular automata, as they also live in a two-dimensional world where patterns consist of colourful pixels.

Spatial games extend evolutionary games to consider that agents have a spatial location determining who they play against. Classically, evolutionary games considered a well-mixed population: every agent played against every other agent sampled randomly from the population. Evolutionary games were born to study the problem of cooperation: why do individuals help others even if that help comes at a cost? From a Darwinian evolutionary perspective that focuses on the survival-of-the-fittest as the single evolutionary mechanism cooperation does not make sense: offering your food to someone incurs an evolutionary cost to you and benefits an individual that is not genetically related to you and, therefore, does not contribute to your fitness. Yet examples of cooperation abide in nature: a bee will sting you to protect its hive, plants share nutrients with their neighbors and humans make truces in the most dire situations.

How can cooperation emerge and survive despite its evolutionary cost? Classical evolutionary games cannot answer this question because cooperation is wiped out under survival-of-the-fittest. Today we now many ways to extend evolutionary theory to account for the emergence of cooperation (see “Five rules for the emergence of cooperation” in this influential book by one of the authors) For example laws, social norms and reputation mechanisms abide in human culture and are some of the most powerful mechanisms for ensuring cooperation. Spatial games are an alternative framework, more primitive someone could say. They simply add a property to an agent, its location, which determines which other agents it plays the game against. This paper was the first work to show that, if agents play only against their neighbors, cooperators can survive by self-organizing into clusters. It also showed that a game with simple rules can lead to chaotic patterns.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

The game-theoretic problem studied in this paper is the Prisoner’s Dilemma (PD). The authors could have chosen another game, there were quite a few in the literature at that point, like the Stag Hunt and the Battle of the Sexes. They chose the PD arguably due to its difficulty: cooperation is impossible to emerge in this game in a well-mixed population (one can prove this using Evolutionary Game Theory). This is how the game goes:

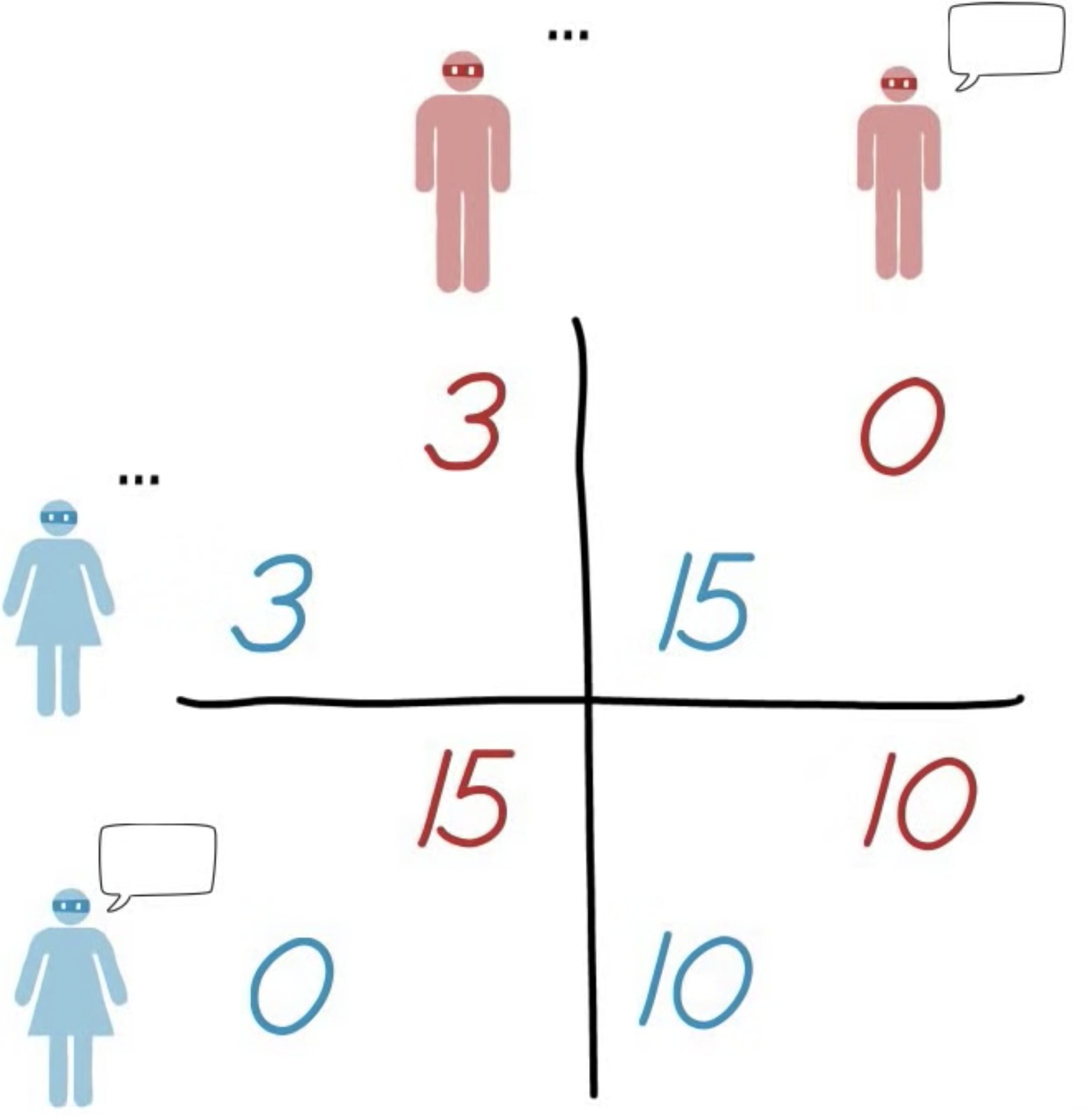

Mary and Bob are in a dire situation: they stole some jewelry and got arrested by the police. The policemen are pretty sure they caught the right culprits but they do not have strong evidence: the jewelry has not been found yet. To find the jewelry and appropriately punish the culprits they play out a trick. Mary, isolated in an interrogation room, is informed that the police has enough evidence against her and Bob to imprison them for three years. Yet Mary can get out of this: if she tells them where is the jewelry and declares that Bob did the robbery, then she will get no prison time and Bob will go to prison for 15 years. Bob is in exactly the same situation. If he snitches on Mary and she does not, he will walk away and Mary will get 15 years. If they both snitch on each other, they will both get 10 years. What should our anti-heroes do?

Mary first thinks that Bob will probably not snitch on her. “The best thing for me to do then is to snitch and get away. And if Bob snitches? Well the best thing to do again is to snitch to get 10 instead of 15”. But Mary realises that Bob is in the same situation. “Bob will snitch too. We’ll have to spend 10 years argueing about this.”

Bob and Mary could have gotten away with 3 years each, the best possible scenario, but, by acting rationally in their own interest, they both get a worse outcome. PD is an example of a game where rationality leads to a worse result than cooperation would.

The payoff matrix of the Prisoner's Dilemma, describing the value of the different outcomes for each player.

The Spatial Prisoner’s Dilemma

In the field of Evolutionary Game Theory games are played by assuming that a population of agents is playing them and seeing which strategies will dominate after some time. There are only two possible strategies: cooperate and defect. In our own story, cooperate would be to not snitch on the other and defect would be to do so. The game is played for multiple rounds and, in each round, two agents are randomly sampled within the population to play against each other. The fitness of each agent is determined by the strategies of the two and the payoff matrix and, at the end of the round, the fittest one gets to impose its strategy on the loser. In this way, the best-performing strategy soon dominates.

The proposal of Nowak and May was rather simple: what will happen if we don’t sample agents randomly but position them in a two-dimensional grid and have them play only against their immediate neighbors? They implemented this by having an agent play against the 8 agents in its Moore neighborhood, calculating their average fitness based on the 8 games and imposing the strategy of the fittest to all of them.

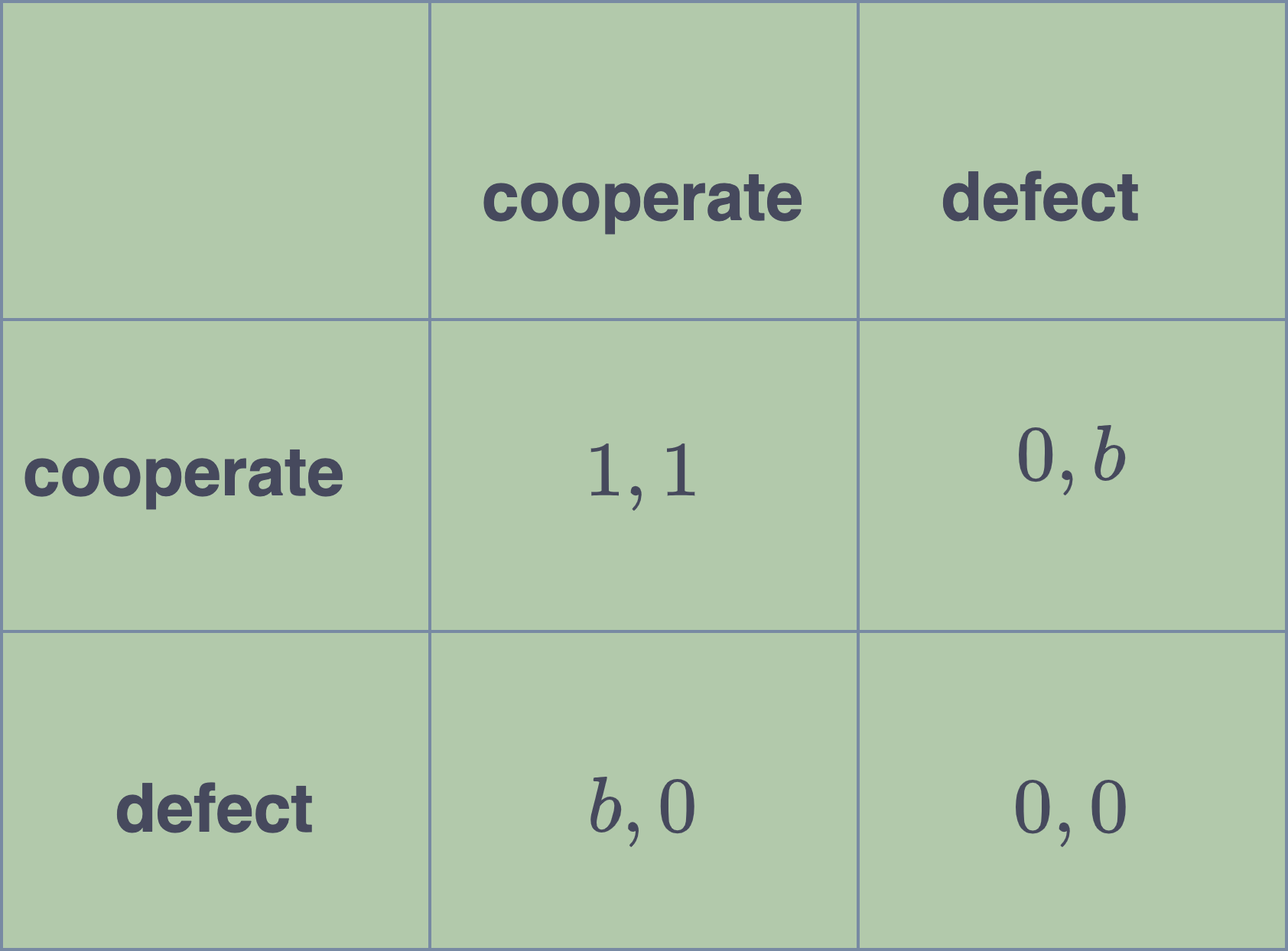

The payoff matrix in their model looks like this:

b is termed the benefit and quantifies the fitness gain of a defector when playing against a cooperator.

The value of benefit determines how beneficial cooperation is and is the most important hyper-parameter of the affecting the dynamics of the game. The higher it is, the more difficult it becomes for cooperators to survive.

Interesting patterns

Cooperators self-organize into clusters

In contrast to the well-mixed case, cooperators in the Spatial Game manage to survive indefinitely. They do so by self-organizing into clusters and pushing defectors on the boundaries. It is easy to see why this meta-strategy does not work in the well-mixed case: if a defector is randomly placed within a cluster it will quickly convert it to defection. This meta-strategy arises only when the value of the benefit is high enough.

Clusters of cooperators when the benefit is 1.77.

Chaotic dynamics

Is it possible to observe chaotic dynamics in this game? All previous studies showed that, eventually, games converge to a fixed point (in the case of PD, one that has only defectors). Yet in its spatial form, there is a regime for the values of benefit that gives pretty fractal patterns.

Chaotic dynamics when the benefit is 1.9.

Conclusion

This is a rather old and influential paper, but I think that the idea that spatial structure matters in adaptive multi-agent systems has to date not been fully exploited. Also one of the fun things with this paper is the fact that it emphasizes the beauty of fractal patterns, which hint to the open-endedness of the system. Open-endedness in MAS is today an objective a lot of people are working on, but we don’t seem to be close to solutions in realistic environments whose dynamics look as impressive as these fractals. This may be a side-effect of focusing too much on the performance of MAS and thus missing out on their intricate temporal dynamics.