He did not remember if he moved in the place because the rent was cheap or it was near his work. They say your capacity for memory shrinks or expands based on what the world expects from you, so his must be the size of an atrophied blueberry by now.

He first noticed the tightness of the situation when his neighbour Lilly complained that his toenails were scratching the polish of her new boudoir. Lying in bed that night and stretching his arm to reach the ceiling, he trapped his elbow in an embarrassing position between the bookshelf and the wall painting. He unavoidably started panicking when he realised that his tea set could only be placed vertically on the kitchen table, the sugar pot necessarily at the bottom for balance. No upcoming guests, he figured.

He then began meticulously measuring every distance in his apartment, noting the dimensions in his notebook. He did not have enough space for a ruler (which should have revealed to him that he did not have enough space), so he used his comb. You would think there were notes in the notebook like “the coat rack is hanging four combs away from the electric heater” and “the sofa’s sturdy leg is three combs to the east of the disk case”, but he was actually measuring in comb teeth. His bed was eight teeth away from Lilly’s window, which explained why soapy droplets woke him up in the mornings of even the clearest skies. Standing five teeth away from his tiny electric bass collection and right next to the wall, the gas stove had left a stain on the wall that he had been until now mistaking for a reproduction of Picasso’s black period (or was it blue?). By that point, he ran out of space on the notebook, itself being two by three teeth wide.

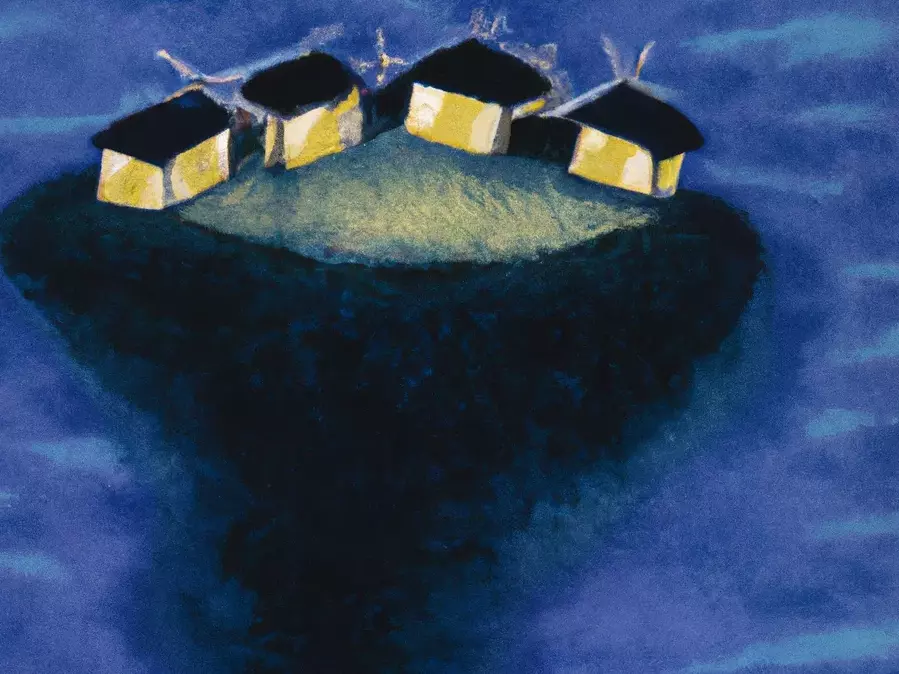

What about vertical space, you say? Making the apartments higher is a grand idea, or so at least agreed with you Steven and his neighbours. Three floors should be ideal, they initially thought, two floors not being worth the construction effort and four seeming unfashionably voluminous for their island’s surface; a Tour Eiffel on our island would Steven mentally note and smirk during their assemblies. Two weeks of cement dust-coated nightmares followed. Boxes of metallic-sounding content, buckets of sickly grey mortar, shaky scaffolds and creamy white paint, smelly sawdust and plastic cables entranced with screwdrivers. With no more than three comb teeth separating their external walls from the salty mouth of the sea, all construction had to take place from within.

When he finally got rid of the last speck of wood skin and looked around from the depth of his soft sofa, Steven felt the weight of a new dimension entering his life. He suddenly had more space for stuff, but more so for thoughts, which became fluffy and sugary. One day Steven woke up with bangs and scratches on the wall. Duncan was building another floor, typical of him, thought Steven who had experienced life prematurely fatiguing his neighbour many times in the past. Seeing Lilly erecting a new floor did not surprise him either. In the past few weeks, he had (secretly as always) watched her sun-deprived fern gradually regressing to the state of a Mediterranean country under foreign capital control; decomposing into a embarrassing brown of questionable future, despite the beauty surrounding it. Upon realising that he could not see Lilly anymore, who was dwelling in the sunshine of her new floor, Steven immediately raised his apartment too. The three of them then entered the mathematically inescapable spiral of a race towards nothing particularly reachable. He was decorating his forty-seventh flour when he realised he did not have enough space for his Swiss cheese plant. The effort of climbing up the stairs was so big that he had ended up inhabiting only the top two stories. This would have not bothered Steven, if it was not for the bar.

When he entered tight situations, Steven liked going to the bar. Oblivious to their unfolding story, the bar did not bother lifting itself, forcing everyone to step down twenty-seven or thirty-six floors, depending on the week. It was standing on the right of his place, which meant that Lilly’s apartment was between his and Duncan’s. From there he could freely (but still secretly) look into Lilly’s room without Duncan blinding him with his torch powered by propane and jealousy. Of course that did not ultimately stop Duncan, who would sometimes spread his umbrella through his window, over Lilly’s sofa and push Steven’s glass one tooth to the left, exactly as much was necessary for dropping it from the bar. This would make the barman very angry, because the whole place would fill with pieces of soda-lime glass and sticky whiskey (for efficiency-related reasons the bar only served high-concentration alcohol).

When Steven left the bar, he felt empty. Looking towards the opposite direction of his apartment, there was only stars and the moon, sometimes. He would then take the comb out of his pocket and carefully position it between the red smudge and the bright spot on the sky. The comb was barely long enough to cover the distance. His finiteness-conditioned mind would then fill with numbers meticulously sketched between every distance measurable forming a fractal mesh that would in front of his eyes regress into a chaos of stars and thoughts with no boundaries to bump into. “That’s why they call it space” he would note to himself and put the comb back to the safety of his warm pocket.